A landmark in the history of books. First printed in 1493, its title in Latin is Liber Cronicarum – Book of Chronicles – but it’s better known in English as the Nuremberg Chronicle, after the city in which it was published. It’s one of the most famous early printed books, and one ofthe first to successfully integrate images and text.

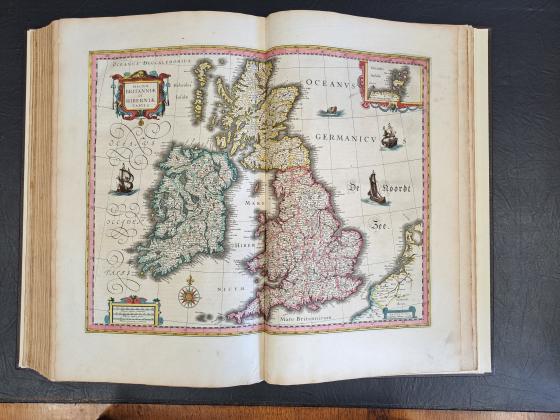

Written in Latin by the German physician and humanist Hartmann Schedel, the Chronicle presents a universal history of the Christian world from the beginning of time to the 1490s, told across almost 700 pages. The narrative is brought to life with more than 1,800 illustrations of Biblical scenes and historical events, including the destruction of Jerusalem. It also features a fascinating map of the known world, showing the Gulf of Guinea as discovered by the Portuguese in 1470 (but with no sign yet of the Americas).

A free city within the Holy Roman Empire, in the late 15th Century Nuremberg was rapidly becoming the centre of a cultural and artistic movement that would become known as the German Renaissance.

The Chronicle was one of the key expressions of this movement. Merchants Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister commissioned its publication from printer Anton Koberger, owner of the largest printing house in the city and indeed the Empire. A German translation was also commissioned, with the two works completed simultaneously on Monday 23 December 1493.

The Chronicle has endured as one of the best-known books of the 15th Century, not least thanks to the beauty and majesty of the illustrations. The Library’s copy – one of around a thousand still in existence – is missing some pages, but is otherwise in fine condition.

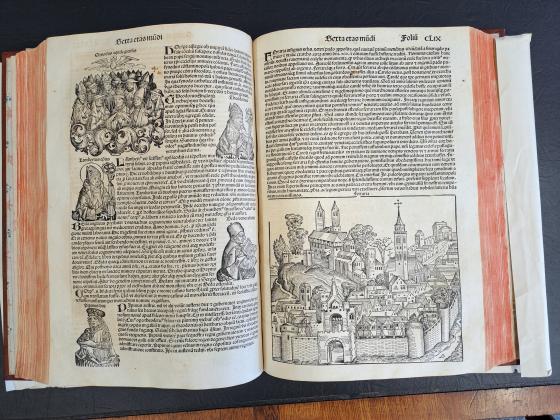

POPE JOAN

The most notorious page of the Nuremberg Chronicle depicts Pope Joan, a female pontiff who supposedly reigned for two years in the mid-9th Century. The story holds that Joan disguised her sex and reigned under the title of John VIII from 855 to 858, with the truth only revealed when she gave birth during the cross procession.

Today the story is known to be entirely fictional, but in the 15th Century it was widely believed to be true, and it’s reported matter-of-factly in the Chronicle as part of its chronology of popes. Over the centuries of religious upheaval that followed, the story became deeply controversial, and many Catholics in particular were outraged by the perceived sacrilege. Some readers crossed out the text about Pope Joan and blotted, burned, or erased the woodcut depicting her, while others simply wrote ‘LIES’ in the margin. At least one reader adopted the unusual approach of drawing a beard on Joan’s face, transforming her into a man.

The Library’s copy is untouched, giving a clear view of Joan’s female countenance and the child in her arms.