With Boundless Curiosity now a month old, Marketing Officer Abi Paine reflects on the exhibition journey, and how much we've learnt about the Library's founders.

A week before the Boundless Curiosity exhibition was due to open in November, the project team gathered for a catch-up meeting in the Board Room. ‘We’re nearly there’ said Adam, our project manager. ‘Does anyone have any last-minute concerns…?’

After spending the best part of a year digging through the archives, piecing together the origin story of the Library, choosing museum items to display, clearing the exhibition rooms and deciding what books to showcase, all of a sudden it dawned on me that in a few days people were finally going to come and look at what we’d created.

‘What if people aren’t actually interested?’ I said.

Items from the Library's archive including the visitors book and receipt for the floor tiles in the entrance hall from 1887

We were deep in our Guille-Allès bubble, and it suddenly seemed possible that people might not be quite as excited as we were about a receipt for the tiles in the entrance hall from 1887, or a copy of the original constitution from 1896. We had immersed ourselves in Thomas and Frederick’s life, through newspaper archives, Library records, New York business directories, exploring the journey that led them to opening the building we now care for so much.

What we discovered was a tale of two men clearly obsessed with learning and knowledge. And with the enlightenment and opportunity it would bring them. Imagine being offered the chance to go to New York at just fourteen years old – swapping the quiet lanes of rural Guernsey for the wide city blocks of Manhattan.

They were best friends, united in purpose.

As soon as Thomas Guille set foot inside the Apprentices’ Library in New York, he made it his life’s ambition to start a Library back home in Guernsey, with his good friend Frederick Allès by his side. As The Star newspaper reported, ‘the two youths were inseparable, wherever duty or inclination led them, whether to a religious service, a scientific lecture, or as more often the case, to the sale room of some book-auctioneer, where many a coveted volume was purchased in prospect of the future Guernsey Library’. They were best friends, united in purpose.

As the senior apprentice, Thomas was allowed to keep his bookcase in his employer’s office, presumably for safekeeping. As noted in John-Linwood Pitts’ book, it didn’t take long for the contents to attract the attention of ‘the literary and scientific gentleman who had business transactions with the firm’. On being informed that they belonged to the apprentice, ‘many a gratifying remark was made as to the excellent judgement shown in the selection’. I bet Thomas was chuffed.

Plate from Guille & Allès' business c.1860, and Frederick Allès' name inside the cover of John J Audbon's The Birds of America

Not satisfied with just theoretical learning, Thomas and Frederick conducted experiments of their own, including constructing ‘a very useful set of apparatus for their chemical laboratory, together with an electrical machine, a galvanic battery, a microscope’, and even a telescope for astronomical observations. I picture them huddled around the table each night, fervently testing out their ideas whilst the city hummed outside.

After working their way up in the business, eventually Thomas and Frederick struck out on their own in New York, and by 1860 ‘Guille & Allès Interior Decorators’ were operating out of a large shop on Broadway and Fifth Avenue in central Manhattan. They were making their fortune as business boomed – but they never lost sight of their Library dream.

Through their incessant energy and dedication to business, they returned to Guernsey with several thousand books. They bought the Assembly Rooms on Market Square, and officially opened the Library in 1882.

They were making their fortune as business boomed – but they never lost sight of their Library dream.

But they didn’t rest there. Thomas was a keen promoter of the work of the Société Guernesiaise and was on its committee; he was honorary secretary of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals; Council member at the Ladies College; member of the committee for the Victoria Cottage Hospital and Convalescent Home; and the first president of the Society of Natural Science, among other roles.

Frederick, meanwhile, continued to seek out rare and valuable books to add to the Library’s collection. He would make special journeys, sometimes on just a few hours’ notice, to London or Paris to secure coveted works that had become available. It was noted that the journeys were ‘labours of love’ and that he undertook these quests gladly, for the good of the Library.

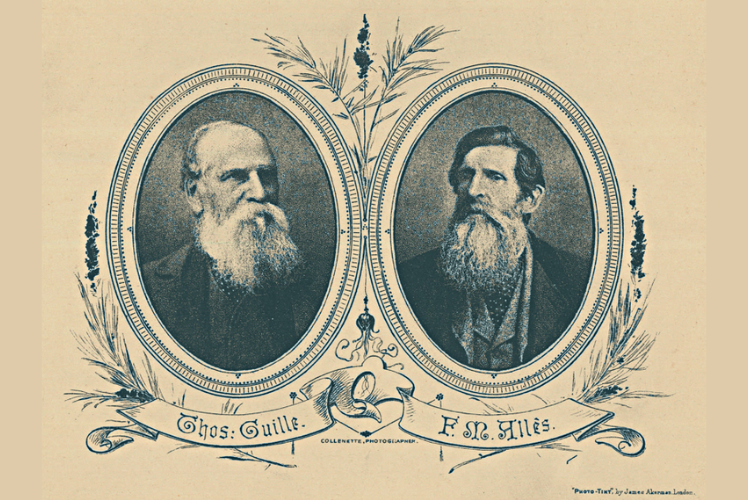

Photographs of Guille & Allès, and a poster from the 1900 lecture series held at the Library

As both men entered their 70s, they remained committed to the idea that the advancement of knowledge was key. They spent much of their time raising awareness of the benefits of the Library, and encouraging people to use it. They wrote frequent letters to the newspaper, listing which new books were added to the shelves, how they had rearranged the rooms or added heating to make visitors more comfortable, and thanking people who had donated items to the Museum on the top floor.

I do find it sad, in a way, that it took the friends so long to fulfil their boyhood dream. They saw fourteen years of Library life before ill health took hold, and they died just over a year apart. From their obituaries we know their deaths were felt as an immense loss to the people of the island. The paper wrote ‘the story of Messrs T Guille and F M Allès is one in which their names are inseparably associated and which for generations to come will be mentioned with gratitude and admiration.’

I feel like we’ve gotten to know Thomas and Frederick as the project has progressed, and I’ve developed such a fondness for them. I think they’d be proud of how the Library has fared through the century that followed, how it developed and now thrives as an integral part of the community. They noted in the Constitution that the Library should have ‘elasticity of adaptation as shall enable it successfully to grapple with the changing necessities and varying requirements of succeeding generations as they pass’. They had the foresight to know that the Library would have to adapt to the people in order to serve them best, and we strive every day to fulfil their wishes 140 years later.

I feel like we’ve gotten to know Thomas and Frederick as the project has progressed, and I’ve developed such a fondness for them.

Once we’d launched the exhibition, the project team made a pilgrimage to Thomas and Frederick’s final resting places. Thomas is buried at Forest Parish Church with his wife Eliza, and Frederick is buried in the family vault at St Peter’s Church. We spent time chatting to the wardens and reading the inscriptions, as well as learning about the history of the churches they belonged to. It felt special to be able to pay our respects and reflect on the story of our founders.

And I needn’t have worried about people being as interested as we are in the story of the Library, and of Guille and Allès. We’ve had a constant stream of visitors to the exhibition since we opened 3 weeks ago, and as I write this, we’re about to host a sold-out lecture on Audubon and The Birds of America, the most precious book in Thomas and Frederick’s collection. People are captivated by the journey of these humble Guernseymen and by what they achieved during their lives. And it’s such a pleasure to play a small part in the Library’s story, helping to secure its place long into the future.

Paying our respects at Guille & Allès' resting places